When the optimial solution to a problem can be expressed as the sum of solutions to subproblems within it, Dynamic Programming (DP) can be a very powerful tool to minimise the amount of duplicated work. Let’s start by looking at a oft used example in DP, the humble Finbonacci Sequence.

Fibonacci Sequence

When talking about DP we often start with the Fibonacci Sequence. We’ll see that that it doesn’t fit all the characteristics of a DP problem, but it does share the property of having a inherently recursive relationship.

I actually quite dislike using the Fibonacci sequence as an example of DP, partly because it’s not actually a DP problem but mainly because if you force it to be, you end up with a MUCH worse solution than if you tackled it procedurally.

So, if we define the Fibonacci sequence as follows:

\[f(n) = \begin{cases} n & n \lt 2 \\ f(n-1) + f(n-2) & otherwise \end{cases}\]Then we may simply wish to represent this directly as code:

function fib(n: number) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

Unpacking the call stack for $n=4$, we’d see the following:

fib(4)

fib(3)

fib(2)

fib(1)

fib(0)

fib(1) <- Duplicate

fib(2) <- Duplicate

fib(1) <- Duplicate

fib(0) <- Duplicate

Which shows many duplicate function calls that grows exponentially with $n$. To solve this in a DP way, there are two approaches, either with memoization (top-down) or with tabulation (bottom-up).

function fibMemo(n: number) {

const cache = {};

function fib(n: number) {

if (n < 2) return n;

if (cache[n]) return cache[n];

cache[n] = fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

return cache[n];

}

return fib(n);

}

Now the call stack for fib(4) is:

fib(4)

fib(3)

fib(2)

fib(1)

fib(0)

fib(1)

fib(2) <- Duplicated call, but exits early thanks to cache

If we introduced tabulation, we might have something that looks like this:

function fibTab(n: number) {

if (n === 0) return 0;

const cache: number[] = [0, 1];

for (let i = 2; i < n; i++) {

const value = cache[i - 1] + cache[i - 2];

cache.append(value);

}

return cache[n];

}

In this case we store all previous values during the function’s execution so they can be retrieved later, but as we know we’ll only ever need the previous two, we could apply that heuristic and simply do:

function fibTab(n: number) {

if (n < 2) return n;

let a = 0;

let b = 1;

let counter = 1;

while (counter++ < n) {

[a, b] = [b, a + b];

}

return b;

}

which then uses constant memory space, lovely.

What both of these approaches do is remove the reevaluation of a previously completed sub-problem. Which is nice.

I complained earlier about using Fibonacci as a DP example, that annoyance comes from the memozied recursive version. It’s extremely wasteful in overall resources and fundamentally slower as each call will require a new memory frame to find the result, when in reality, you just need to track two variables..

Dynamic Programming Characteristics

Unlike other programming challenges that we face, there is no standard mathematical formulation for a Dynamic Programming problem, instead we must identify them by their characteristics and apply some ingenuity to discover a result. The characteristics we’re looking, broadly speaking fall into the two categories:

- That the overall solution we’re looking to optimise can be described in terms of optimising problems within it, there is an “optimal substructure”

- That there exists some overlapping subproblems

With the above definition, we see that the Fibonacci sequence doesn’t really have any question of optimality, it’s just caching results from a subproblem. Let’s take a look at an example that does.

The Stagecoach Problem

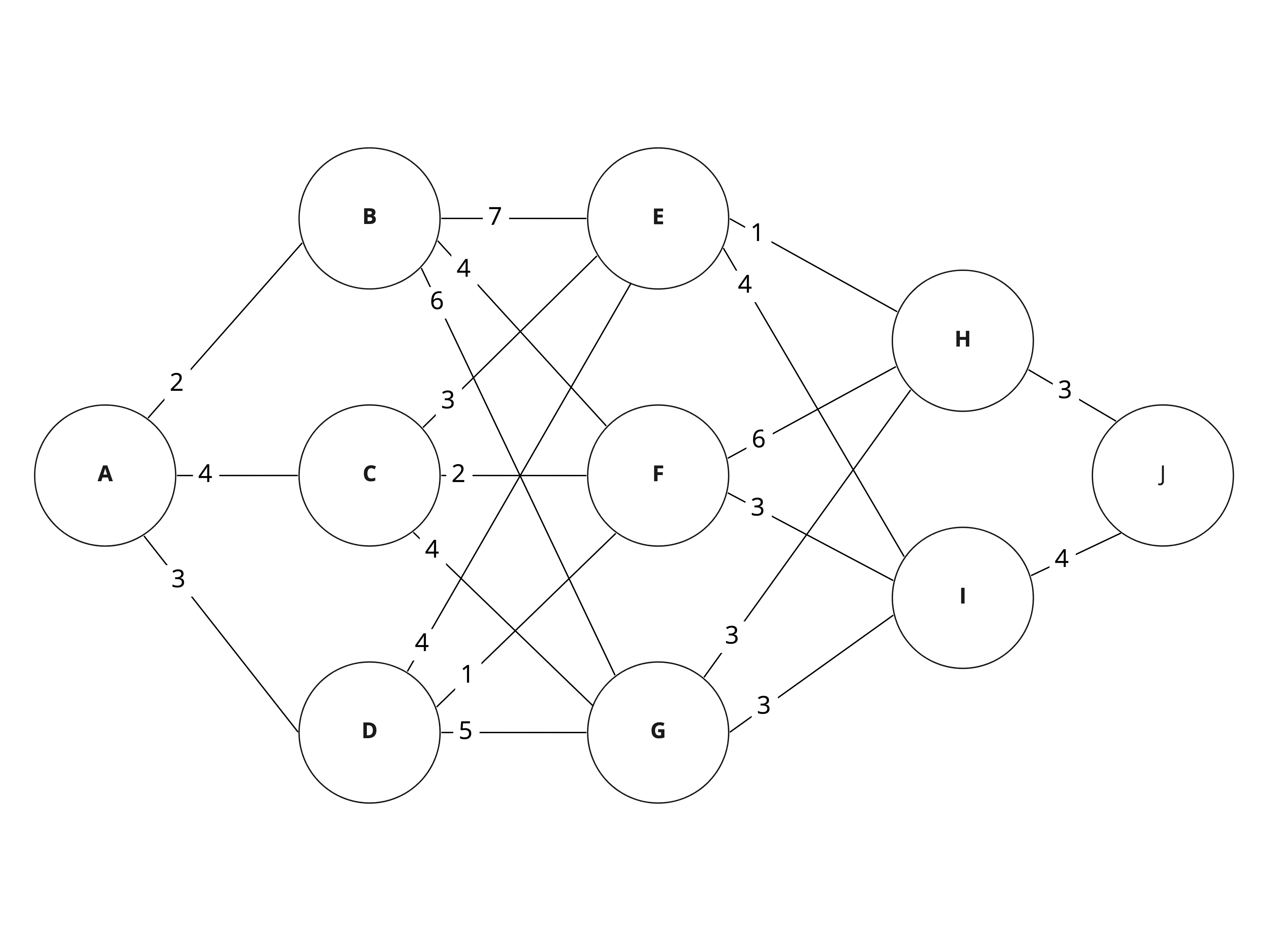

This is a classic problem from the world of dynamic programming. It details a situation in which a “fortune teller” wishes to travel across America via stagecoach when it was unsafe to do so. To compensate for this, the stagecoaches would offer life-insurance policies to their customers. Thinking they would have done their research, the fortune teller decides that the safest route must be the one along which they would spend the least on insurance costs.

So then the question, how can we find the cheapest route? Well… we could enumerate every possible route, but that doesn’t appeal.

If we were to take the naive approach and simply select the cheapest route at each node, we would follow the path A→B→F→I→J for a total cost of 13. However if we were to instead pay more earlier, we could save money later. If we substituted the first three steps with A→D→F and keep the rest the same, the total cost becomes 11!

How does this problem fit with the two characteristics outlined above?

Optimal substructure

We can see that to find the most efficient node from A to J, we’ll need to travel along paths that are themselves the most efficient from that point. For example, if we arrive at node F, then the cheapest path to our destination would be I→J at a cost of 7, as opposed to H→J at a cost of 9. It wouldn’t make sense for us to continue along worst part.

Overlapping subproblems

From the description previously supplied, we can begin to describe our problem in a recursive manner. We know that to find the most efficient path from node $N$, we’ll need minimise the $cost + F(N_{neighbour})$, i.e. the most efficient path from a neighbour plus the cost of us getting there.

As code, we may write something similar to what we’ve seen before:

interface WeightedGraph {

[key: string]: [string, number][];

}

function stagecoach(graph: WeightedGraph, root: string) {

const solve = (node: string) => {

if (graph[node].length === 0) return 0;

const remainingCosts: number[] = graph[node].map(([childNode, cost]) => {

return cost + solve(childNode);

});

return Math.min(...remainingCosts);

};

return solve(root);

}

const graph = WeightedGraph = {

A: [

["B", 2],

["C", 4],

["D", 3],

],

...

}

solve(graph, "A")

The above solution does not cache any of the results as it goes, and as a result revaluates the same paths multiple times, causing 49 calls to solve. By introducing a memoized version, that number drops to 9, one for each node in the tree.

function stagecoachCache(graph: WeightedGraph, root: string = "A") {

const cache: { [key: string]: number } = {}; // NEW

const solve = (node: string) => {

if (graph[node].length === 0) return 0;

if (cache[node]) return cache[node]; // NEW

const remainingCosts: number[] = graph[node].map(([childNode, cost]) => {

return cost + solve(childNode);

});

cache[node] = Math.min(...remainingCosts); // NEW

return cache[node]; // NEW

};

return solve(root);

}

And that’s a whistle stop tour of dynamic programming! If a problem can framed as finding the optimal solution to overlapping subproblems, then dynamic programming your friend.