So far we’ve introduced the problem, generated a random solution, then applied a hill climbing algorithm to improve the overall solution with the simplest possible move.

And you know what, it does pretty well! Especially considering that the deterministic approach is non-tractable, getting a reasonably good solution in a faction of a second isn’t too bad.

Introducing 2-opt

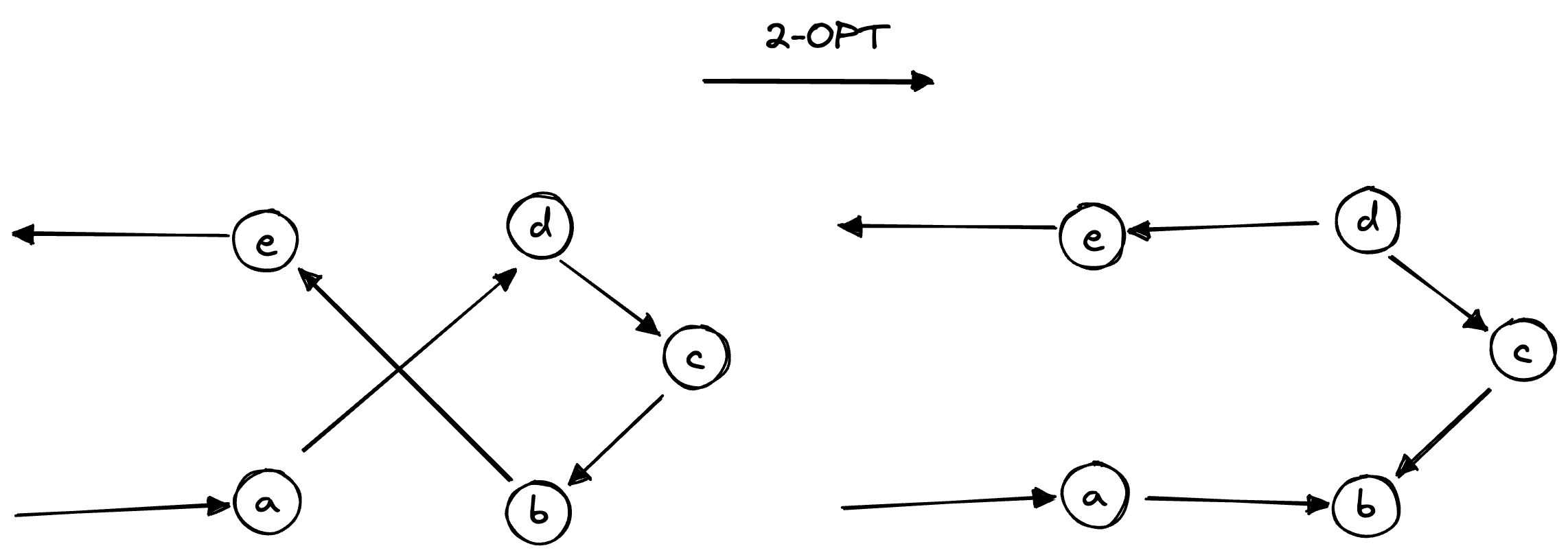

So, what can we do from here? Well, the first thing I’d like to do is introduce a new movement operator, called 2-opt. This is a movement that is designed to undo sections that cross-over themselves, netting an overall reduced distance travelled.

This is a movement that is currently impossible with the single move that we have, as it’d need to occur in two steps, with the first being a worse solution. But what are we actually doing here? If we look at the two paths, we have a - d - c - b - e then a - b - c - d - e, the change that we actually make is the sub-path d - c - b is reversed, but left in the same place.

As code, we might write a new movement that looks like this:

const twoOptSwap = <T>(arr: T[], a: number, b: number): T[] => {

return [

...arr.slice(0, a),

...arr.slice(a, b).reverse(),

...arr.slice(b)

];

};

const twoOpt: Move = {

apply(solution) {

const currentPath = solution.getPath();

for (let a = 0; a < solution.cities.length - 1; a++) {

for (let b = a + 1; b < solution.cities.length; b++) {

const swappedPath = twoOptSwap(currentPath, a, b);

const candidateSolution = solution.withNewPath(swappedPath);

if (candidateSolution.cost() < solution.cost()) {

return candidateSolution;

}

}

}

// no better solution was found

return solution;

},

};

while we change the solution class to expose some handy methods for accessing and setting a new path, guaranteeing immutability.

class Solution {

...

withNewPath(cities: City[]): Solution {

const trip = new Trip(cities);

return new Solution(this.cities, trip);

}

getPath(): City[] {

return [...this.trip.cities];

}

...

}

Lovely!

But you may have noticed that we now have two possible moves that we can apply to our solution, and only one interface to call only one, what gives? Well, now we can introduce a RandomMover, which picks and applies one of the moves entirely at random.

const MOVES = [moveCity,twoOpt];

const randomMove = () => MOVES[randomInt(MOVES.length)];

const randomMover: Move = {

apply: (solution: Solution) => {

return randomMove().apply(solution);

},

};

I didn’t like this hill anyway

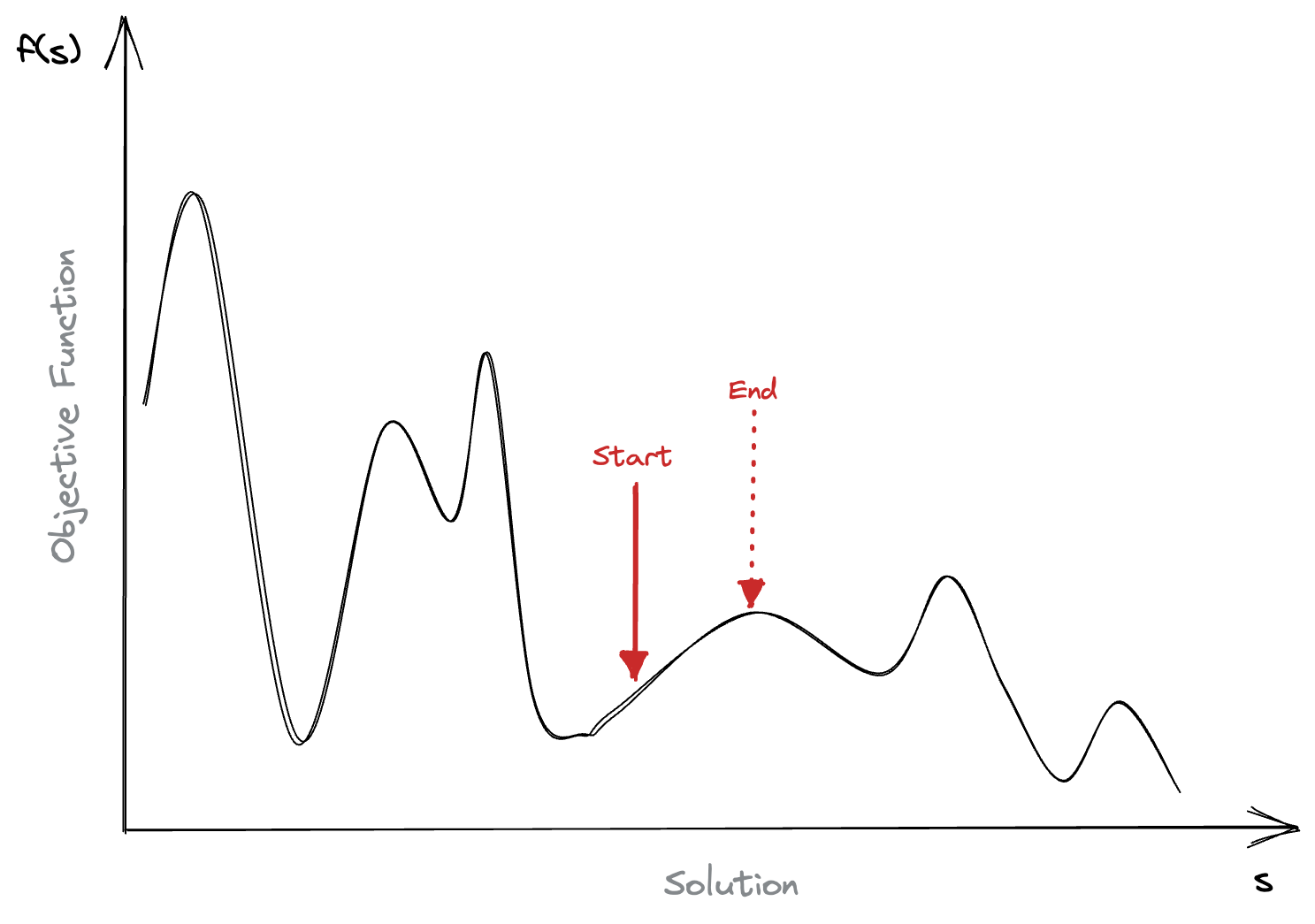

So we’ve introduced a new move that will help get us untangled, but we still have quite a big problem. The search space is large, how can we insure that we’re not stuck in a local minima / maxima? What if the hill that we’re currently trying to climb, is just a bad hill?

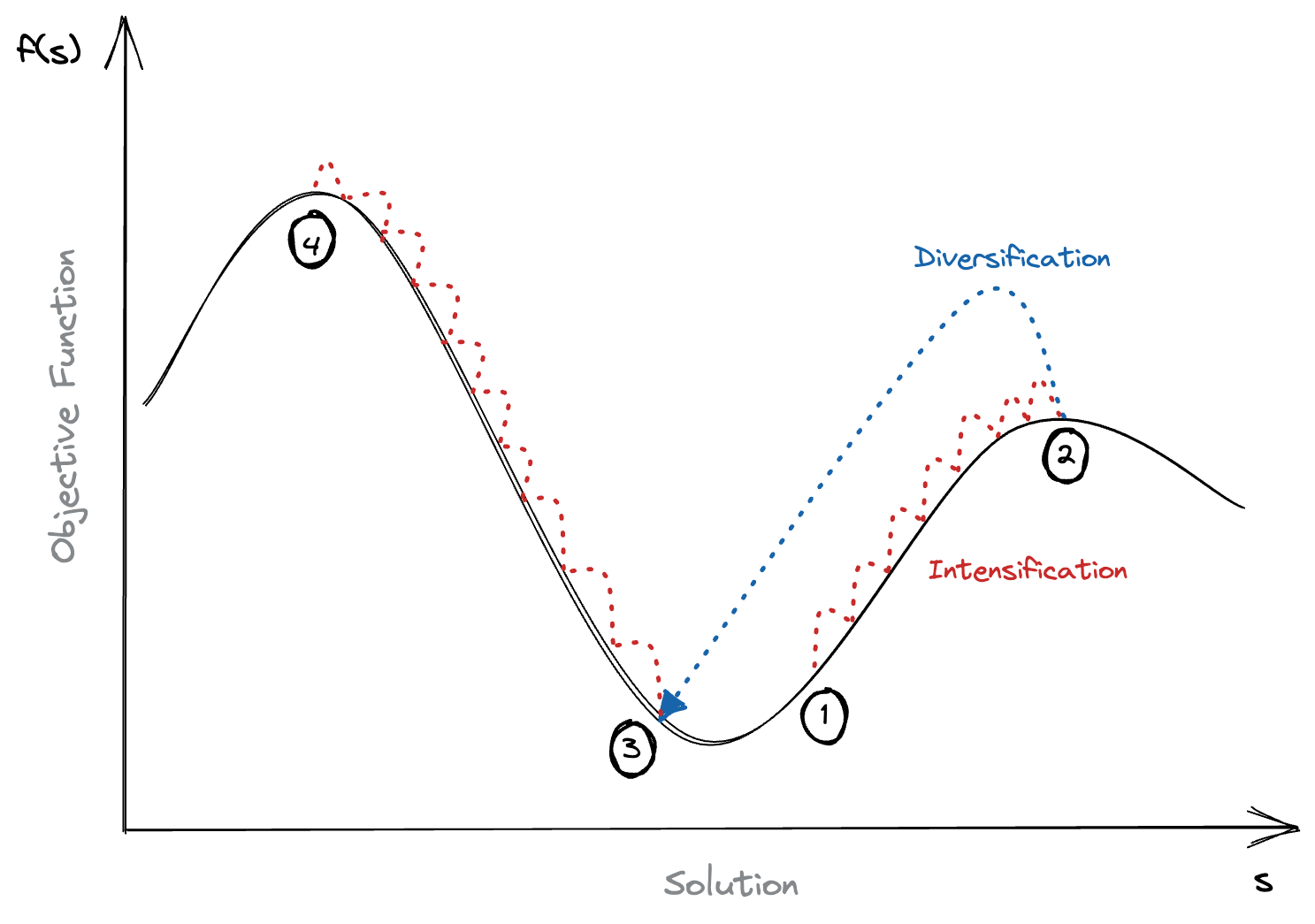

We’ve seen that hill-climbing is really good at intensification, if you have a pretty good starting point then you can be confident that you’ll walk away with a better solution. But as we can never be certain that we’ve climbed the highest peak, what if we looked further afield?

To do so, we introduce the concept of a neighbourhood search, rather than just search locally, let’s explore a little further away and see what happens. To do this, we need to apply a diversification step.

So what does this look like? Well, first of all we need a new Runner. The current one is pure hill climbing, let’s extend it. This diversification is often referred to a “destructive” move, as we’re taking something seemingly good and making it worse.

type RunnerConfig = {

construction: Move;

stoppingCriterion: StoppingCriterion;

move: Move;

};

type NeighbourHoodConfig = RunnerConfig & {

staleMoveLimit: number;

};

class Runner {

run(

cities: City[] = ATT_48_CITIES,

config: NeighbourHoodConfig,

initialSolution?: Solution,

callback: (solution: Solution) => void = () => {}

) {

const emptySolution = Solution.default(cities);

let bestOverallSolution =

initialSolution || config.construction.apply(emptySolution);

let movesSinceBest = 0;

let currentBestSolution = bestOverallSolution;

while (!config.stoppingCriterion.shouldStop()) {

const candidateSolution = config.move.apply(currentBestSolution);

if (candidateSolution.cost() < currentBestSolution.cost()) {

movesSinceBest = 0;

currentBestSolution = candidateSolution;

if (currentBestSolution.cost() < bestOverallSolution.cost()) {

bestOverallSolution = currentBestSolution;

}

callback(currentBestSolution);

}

if (movesSinceBest++ >= config.staleMoveLimit) {

currentBestSolution = this.destroySolutionSegment(currentBestSolution);

}

}

return bestOverallSolution;

}

destroySolutionSegment(solution: Solution): Solution {

// destroys up to half of the current solution

const currentPath = solution.getPath();

const a = randomInt(Math.round(currentPath.length / 2));

const b = a + randomInt(Math.round(currentPath.length / 2));

return solution.withNewPath([

...currentPath.slice(0, a),

...shuffle(currentPath.slice(a, b)),

...currentPath.slice(b),

]);

}

}

Neat! And in practice? Well, have a play and see for yourself :)

Comparing the hill climbing and the neighbourhood runs, you should find that we more frequently end up with better solutions form the neighbourhood search! That doesn’t stop you being lucky with the pure hill climbing however, you could very well just guess the best hill to start on.

So far we’ve been able to create solutions to a problem that is deterministically not-ideal to solve, all in javascript in a fraction of a second. Neat huh?