Web frameworks like Django or Ruby on Rails come with “batteries included”. They do a lot of stuff straight out of the box without you needing to spend too much time thinking about it, leaving you free to focus on problems that are more closely aligned to the reason you’re working with them in the fist place. One of these is object access and persistence. Django’s Models and Rails’ Active Records are the APIs around which objects are defined, stored, and accessed.

But what if you can’t, or even simply don’t want to use them? Maybe you’re learning a new tech which doesn’t have this feature, maybe you’re building your own framework, or maybe you’re simply working in an environment that prohibits their use? (Squeezing a big web framework into a lambda is tricksy.) You’ll sidestep the constraints that such frameworks impose, but you’ll have to solve a lot of problems yourself, and one tool that might help with that, is the Repository.

A simple blog

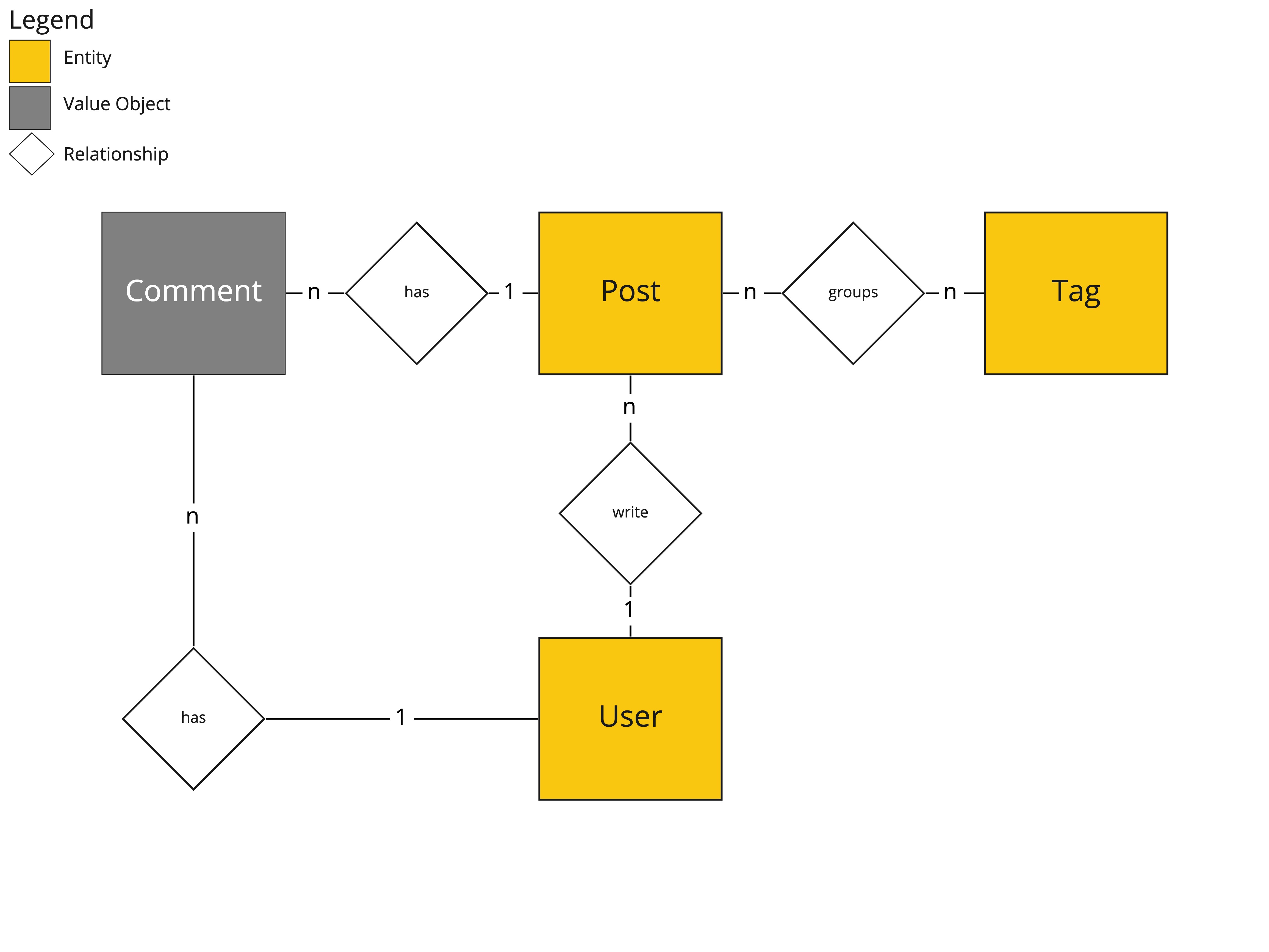

Let’s start with the basic example of what a blog might look like. Before we can begin any modelling we need to have some notion as to what it actually is that we’re modelling, and for that we’ll use an Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD).

Lovely! So it’s a pretty simple blog, there are posts, tags, comments and users. But nothing mentions the word aggregate. How do we know where to start? What even is it?

A DDD aggregate is a cluster of domain objects that can be treated as a single unit. - Martin Fowler

A great example of this is a shopping basket and items, where one adds and removes items from the basket. In this case, it can be useful to think of the items in terms of the basket they’re in, rather than the items themselves.

Generally deciding upon aggregates is an exercise in exploratory thinking; the answer may not be as obvious as it seems (and if it is obvious, you’re probably better off doing the thinking anyway!). You can do this as a group, or spend time mulling it over with a coffee.

In our case then, what do we have? Well, arguably one aggregate and two standalone domain objects. i.e. comments don’t make much sense without a post, so perhaps they belong under a Post aggregate? Tags and users on the other hand seem like independent entities, so let’s keep them like that.

Brace yourself, TypeScript incoming

Above we said the repository is a pattern for access and mutating domain aggregates. Before we can really see how it works, we’ll need to have an idea about the other objects in the domain.

// where would the internet be without comments?

// (notably, this blog does not have comments... 👀)

interface Comment {

author: User;

content: str;

}

// posts have a single author, and can have n tags or comments

interface Post {

title: str;

content: str;

comments: Comment[];

tags: Tag[];

author: User;

}

// tags can be used to group posts together

interface Tag {

name: str;

}

// a very simple user object

interface User {

email: str;

username: str;

}

Now we’re aware of our domain objects, let’s quickly see what saving a comment to a relational database using node-postgres might look like:

// domain object

class Comment {

author: User;

content: str;

post: Post;

constructor (author: User, content: str, post: Post) {

this.author = author;

this.content = content;

this.post = post;

}

async save(client: pg.Client) {

// post_id and author_id are not foreign keys

const text = `INSERT INTO comments(content, author_id, post_id) VALUES ($1, $2, $3)`;

const values = [this.content, this.author.email, this.post.title];

// probably want some error catching here

await client.query(text, values)

}

}

// app.js

const express = require('express')

const app = express()

const port = 3000

app.post('/api/comment/', (req, res) => {

const author = request.body.author;

// having this code here just adds noise, you get the idea

const post = new Post(...)

const comment = new Comment(

author,

req.body.content,

post

)

comment.save();

res.send('""');

res.status(201).end();

})

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`App is listening at http://locahost:${port}`)

});

To summarize the above, we have some API endpoint that we can do a POST request to, and it’ll convert the body to domain objects and then save it. Easy.

So what’s the issue here? Well part of the problem is that our domain object is doing a lot. There’s a blurring of the boundaries between the domain layer and the data layer, but we’re also relying on our persistence engine to protect our state consistency. What if the post gets deleted? Will comments be cleaned up too? That really just depends on the DB and its configuration, and if we need to change our DB for some reason, then what?

Enter the repository

It’s important to bring up a simple rule when working with aggregates and repositories. Each repository should reflect one aggregate and no more. With that in mind, we might end up with something that looks like this:

interface PostRepository {

async save(post: Post) => void;

async getPost(postId: string) => Promise<Post | undefined>;

async getByTag(tag: Tag) => Promise<Post[]>;

addComment(comment: Comment) => void;

}

interface TagRepository {

async save(tag: Tag) => void;

async getTag(name: string) => Promise<Tag | undefined>;

}

interface UserRepository {

async save(user: User) => void;

async getUser(email: string) => Promise<User | undefined>;

}

Great! Let’s just focus on the interesting one, the PostRepository. If we’re interacting with all grouped entities from the aggregate, how will we know what to do? How will we know what to save, update, or delete? We could figure it out at save time, but it’s more efficient to keep track of changes to the aggregate within the aggregate itself, and then act on this.

interface CommentEvent {

type: 'add' | 'remove' | 'delete'

id: string;

}

class Post {

private events: CommentEvent[];

constructor(...) {

// set properties from constructor arguments (not doing so here because

// it's a distraction)

this.events = [];

}

addComment(comment): void {

this.comments.push(comment);

this.events.push({ type: 'add', id: comment.id });

}

getEvents(): CommentEvent[] {

return this.events;

}

}

So fleshing this out and updating our view we get:

class PostgresPostRepository implements PostRepository {

constructor() {

// establish the connection and set here

this.client = ...

}

async save(post: Post) => {

// perform all operations inside a transaction

try {

await this.client.query('BEGIN');

// save the post object first

const operation = post.id ? 'UPDATE' : 'INSERT';

const postText = `${operation} INTO post(title, content, author) VALUES ($1, $2, $3)`;

const postValues = [post.title, post.content, post.author]

await this.client.query(postText, postValues);

// now build the queries for all domain objects under it

const eventPromises = post.getEvents().map(

event => {

// perform the appropriate query for this event

}

)

await Promise.all(eventPromises);

await this.client.query('COMMIT');

} catch (e) {

await this.client.query('ROLLBACK');

} finally {

this.client.release();

}

}

// other methods left out!

}

// app.js

const express = require('express')

const app = express()

const port = 3000

app.post('/api/comment/', (req, res) => {

const postRepository = new PostgresPostRepository();

const comment = new Comment(req.body.author, req.body.content);

const post = postRepository.getPost(req.body.postId);

post.addComment(comment);

postRepository.save(post);

res.send('""');

res.status(201).end();

})

app.listen(port, () => {

console.log(`App is listening at http://locahost:${port}`)

});

Well, that’s a lot more complicated isn’t it? What have we achieved with this trade off?

- We’ve made our domain object more easily testable, as any modifications to it are tracked in data, not in some external service.

- We’ve decoupled our data layer entirely from our domain, meaning that we only need to look at the behaviour within the repository to understand what’s going on in our system, and nowhere else.

- This means that if we needed to change our data layer for some reason (moving to Aurora, or Redis, etc etc) we need only change the repository. As long as it implements the same interface, we won’t need to change any of code! (See hexagonal architecture for more.)

As with the application of any design pattern, there are always trade offs. If you’re working with objects that don’t lend themselves to aggregates then don’t try to force them into one! For most applications however, the domain is sufficiently complex that doing so will be beneficial.