Databases have changed a lot over the years, from the first relational databases coming into being in the early 1970s to the distributed, eventually-consistent, highly available key value stores we can use today. Relational databases still exist of course (and some can even be described in similar ways), but when talking about database engines, the phrase “ACID Compliant” often comes up.

ACID

ACID is of course, an acronym. It stands for Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability.

Atomicity

An operation is said to be atomic if it either succeeds or fails completely. It cannot exist in a “dirty” state. This means that even if it does succeed, at no point were any partial writes visible to any other operation on the database, and if it fails, the database guarantees that it will undo everything that was done.

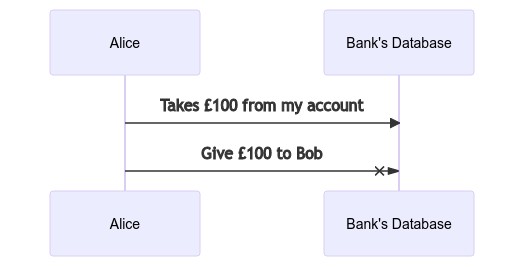

Consider the following basic example. Alice wants to transfer Bob £100, she does this by first withdrawing the money, and then sending it to Bob. But what happens if the transfer fails as shown here? Alice’s money just.. disappears? The two operations are not grouped atomically.

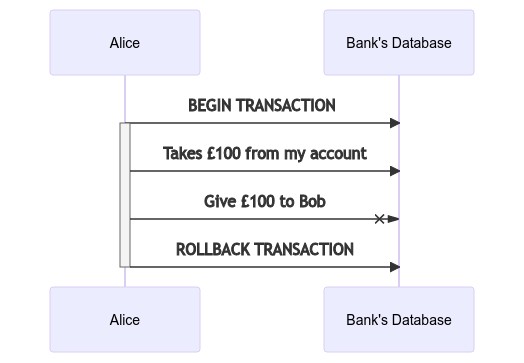

To solve this specific problem, many databases provide the notion of a transaction. A transaction is a way of grouping multiple operations together. Either they are all successful and are committed or none of them are and they are rolled back.

In this instance Alice is performing these operations within a transaction. As such, no modifications are available unless all of them succeed and the database is told to commit them. As one fails, the commit doesn’t happen, and Alice doesn’t lose any money.

Her transfer of money is now atomic.

Consistency

Consistency in ACID is very different to the Consistency in CAP theory (I’ll most likely write a ‘what is’ on that too.), in that an operation can only move the database from one valid state to another. Continuing with the banking example however, the database itself does not concern itself with knowing that Alice’s money can’t simply disappear - this is a rule imposed on it by us, the humans who created the app.

The consistency guarantee from a database is more to do with the invariants it supports, but are defined by us. For example, our bank might decide that it only supports simple checking accounts, and as such no account can go below zero. To ensure this, we might add a constraint on the data to say it must be equal to or greater than zero. The fact that the database will support this constraint is great, but the onus is still on the developers in the domain to understand just what these invariants are, and the tool that we’ll use to support and enforce them. We don’t have to use a constraint like this; we could do it using a conditional write.

But hey, if the system supports such invariants then why not! (Other than splitting domain logic between your application layer and data persistance layer of course.)

There are other types of patterns that a database can guarantee to support, things like valid foreign keys, cascading deletes, triggers, but they all amount to the same thing. We define what a valid state is, and the database provides tools to help support them.

Isolation

THIS ONE IS THE BIG ONE.

Isolation refers to how one operation might impact another, and different operations may have different levels of isolation between them. What happens if you update a row as someone else is trying to read from it? Or both of you are updating the same thing at the same time? There are many different strategies for handling this, and different databases will employ different ones that best fit their needs.

Isolation levels of an operation are crucial to understand if you want to avoid some extreme headaches down the road, and there are several…

- Serializable: concurrent operations appear as if they were performed one after the other

- Repeatable reads: specified data is viewed in the same state it was in at the start of the operation

- Read committed: read operations always return committed values

- Read uncommitted: read operations can return uncommitted values

Let’s say our bank’s database is distributed, i.e. that not all the data is on one server but is instead split across several.

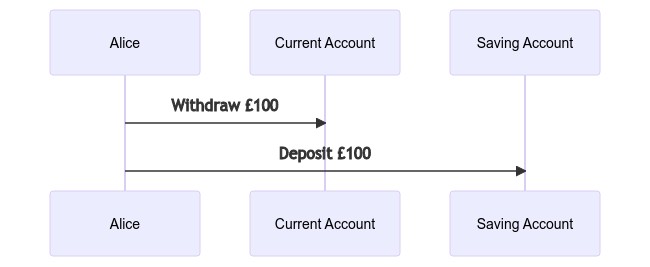

If Alice wanted to move another £100 from her current account to a savings account, it might look something like this:

So what happens if Alice requests this transfer, while simultaneously refreshing her accounts to see their total value. From the database’s perspective, we have three operations that we’re performing:

- As a transaction, move money from Alice’s current account to her savings

- Read the current total of Alice’s current account

- Read the current total of Alice’s savings account

If these operations shared a read-committed isolation level, then there are four possible outcomes:

- The transaction completes, followed by the two reads

- Alice reads the value in her current account, then the transaction completes, then her savings account

- Alice reads the value of her savings account, then the transaction completes, then her current account

- Alice reads both accounts, then the transactions completes

For Alice, there are four corresponding outcomes.

- Everything is expected, her current account has lost some money and the savings account has increased, great.

- Her current account looks as though it still has the same amount of money in it, AND her savings account has increased?!

- She sees her savings account without the extra money, AND her current account is now reduced?!

- Finally, she sees no change and will simply refresh.

As you can see, this can get quite complicated quite quickly. Even more so when we consider that some database vendors claim to support one isolation level when in fact it’s something else..

Some popular databases, such as Oracle 11g, don’t event implement it. In Oracle, there is an isolation level called “serializable”, but it actually implements something called snapshot isolation, which is a weaker guarantee than serializability. - Designing Data-Intensive Application, Martin Kleppmann

Durability

The simplest of the components, Durability is the description of a database’s ability to support you being able to read the data in the same way you left it. That is - it will persist in spite of hardware or network failures. Just how it does this is dependant on the system in question, but often there is a Write Ahead Log (WAL) involved.

Summary

Databases have gotten so complex and varied that ACID compliance doesn’t really mean that much when describing them. Even those who have the same database type may go about solving the same problem differently, each introducing its own complications.

ACID remains useful however in reminding the user what considerations we should be having when interacting with a database.

How well does it persist data? Can it help me maintain my domain invariants? Do I want it to? How will these operations interact with one another? etc etc.

Rather than using “ACID compliant” as a seal of approval from the data storage gods, it would be better for us to peer under the hood at what’s actually going on, empowering us to choose the right technologies for our domains, or conversely, modify our domain behavior to work with the technology.